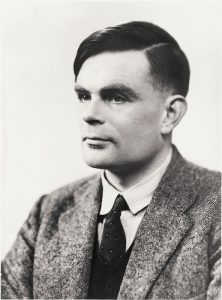

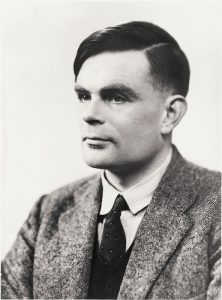

Bletchley Park (or ‘Station X’) near Milton Keynes was the secret site that housed the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) during World War II, which regularly penetrated the secret communications of the Axis Powers, most importantly, the German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers. Among its most notable early personnel was Alan Turing, a Cambridge genius who broke the Enigma naval code, saving countless thousands of lives. Turing is credited with helping to shorten the course of the war by at least two years which may have saved an astonishing 20+ million lives. He is also widely considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence.

We visited Bletchley Park in early November, but first let me explain what went on there, a little about Alan Turing and his colleagues and the contribution he/they made to winning the war, using parts of various articles that I have stitched together:

The Queen visited Bletchley Park on 15 July 2011. She said, ‘It is impossible to overstate the deep sense of admiration, gratitude and national debt that we owe to all those men and, especially, women. They were called to this place in the greatest of secrecy – so much so that some of their families will never know the full extent of their contribution.’

Professor Richard Holmes, a military historian, said, ‘The work here at Bletchley Park … was utterly fundamental to the survival of Britain and to the triumph of the West. I’m not actually sure that I can think of very many other places where I could say something as unequivocal as that. This is sacred ground. If this isn’t worth preserving, what is?’

The rather ugly mock-Tudor, mock-Gothic, red brick mansion, framed by aged trees and with a picturesque pond, has become familiar from TV documentaries and Hollywood films. Perhaps a hundred yards away, the bucolic landscaping comes to an end, with prefab-looking buildings crammed together and labeled things like “Hut 6” or “Hut 8.” Here, in drab, cigarette smoke-stained wooden rooms, about 9,000 mathematicians, linguists, cryptographers, clerks and classicists worked around the clock throughout the war to break German codes.

Germany’s Army, Air Force and Navy transmitted many thousands of coded messages each day during World War II. These ranged from top-level signals, such as detailed situation reports prepared by generals at the battle fronts, and orders signed by Hitler himself, down to the important minutiae of war like weather reports and inventories of the contents of supply ships.

Alan Turing helped crack the Nazi military’s encryption device, Enigma. The Enigma was a typewriter-like cipher machine which incorporated three adjustable rotors and a patchboard providing billions of possible code settings. The rotors and patch board settings were changed daily and the German military assumed there simply wasn’t enough time for the settings to be broken before the codes were changed again at midnight. Turing’s breakthrough came from observing that morning U-boat communications included a weather report, a pattern to be exploited. He designed a machine called a ‘Bombe’ that could quickly sort through the millions of remaining possibilities to divine the code. The first of many, the bombe machine set the stage for a massive operation that would eventually crack up to two messages a minute.

Turing went on to personally break the more advanced four-rotor naval Enigma code used by the U-boats preying on the North Atlantic merchant convoys. It was a crucial contribution. The convoys set out from North America loaded with vast cargoes of essential supplies and troops for Britain, but the U-boats’ torpedoes were sinking so many of the ships that Churchill’s analysts said Britain would soon be starving.

Turing went on to personally break the more advanced four-rotor naval Enigma code used by the U-boats preying on the North Atlantic merchant convoys. It was a crucial contribution. The convoys set out from North America loaded with vast cargoes of essential supplies and troops for Britain, but the U-boats’ torpedoes were sinking so many of the ships that Churchill’s analysts said Britain would soon be starving.“The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril,” Churchill said later. Just in time, Turing and his group succeeded in cracking the U-boats’ communications to their controllers in Europe. With the U-boats revealing their positions, the convoys could dodge them in the vast Atlantic waste.

Thanks to Turing and his fellow codebreakers, much of this information ended up in allied hands – sometimes within an hour or two of it being transmitted.

The contributions of Bletchley Park’s Codebreakers to the outcome of World War II are now globally recognised and include:

* Location of the U-Boat packs in the Battle of the Atlantic

* Identifying the beam guidance system for German bombers

* The Mediterranean and North African campaigns, including El Alamein

* Launch and success of Operation Overlord, including breaking German Secret Service Enigma, complementing the Double Cross operation which misled Germany on the intended target for D-Day

* Helping to identify new weapons including German V weapons, jet aircraft, atomic research and new U-Boats

* Analysis of the effect of the war on the German economy

* Breaking Japanese codes

* The outcome of the war in the Pacific.

At its peak, around ten thousand people worked at Bletchley Park and its associated outstations but most government officials and British naval officers believed the vital information was coming from an MI6 master spy codenamed “Boniface” who reportedly controlled a network of agents throughout Germany. Boniface and his team of spies were entirely fictional. One of those who knew the truth was the future author of the James Bond novels, Ian Fleming, who was then working as a lieutenant commander in Britain’s naval intelligence division. Fleming was involved in devising operations based on intelligence received from Bletchley Park, but judging from his diary entries at the time, it is clear that he and Turing didn’t see eye to eye. “One of the reasons how we know Turing was so heavily involved with MI6 during the war is due to Fleming’s diaries,” says Graham Moore, scriptwriter and producer of The Imitation Game. “Most of the time he’s writing about how annoyed he is with Turing. Fleming was regularly proposing plans and Turing was apparently in a position to be able to reject them. Fleming makes it clear he doesn’t like the look of him. There’s a memorable extract where he writes ‘Turing came in like an undertaker’ and shot down whatever he was saying. One imagines they were two very different sorts of British gentlemen.

In 1946 Alan Turing was appointed an OBE but his Bletchley Park colleague, Max Newman, felt that it was inadequate recognition of Turing’s contribution to winning the war, referring to it as the “ludicrous treatment of Turing” and he refused his own awarded OBE six months later in protest. Today, an OBE does seem rather minimal recognition for one of Britain’s greatest war heroes who, as Winston Churchill would later recall, made the single biggest contribution to the Allied victory in World War II.

Alan Turing: The codebreaker who saved ‘millions of lives’

Prof Jack Copeland

Turing stands alongside Churchill, Eisenhower, and a short glory-list of other wartime principals as a leading figure in the Allied victory over Hitler. There should be a statue of him in London among Britain’s other leading war heroes.

Some historians estimate that Bletchley Park’s massive codebreaking operation, especially the breaking of U-boat Enigma, shortened the war in Europe by as many as two to four years.

If Turing and his group had not weakened the U-boats’ hold on the North Atlantic, the 1944 Allied invasion of Europe – the D-Day landings – could have been delayed, perhaps by about a year or even longer, since the North Atlantic was the route that ammunition, fuel, food and troops had to travel in order to reach Britain from America.

Harry Hinsley, a member of the small, tight-knit team that battled against Naval Enigma, and who later became the official historian of British intelligence, underlined the significance of the U-boat defeat.

Any delay in the timing of the invasion, even a delay of less than a year, would have put Hitler in a stronger position to withstand the Allied assault, Hinsley points out.

The fortification of the French coastline would have been even more formidable, huge Panzer Armies would have been moved into place ready to push the invaders back into the sea – or, if that failed, then to prevent them from crossing the Rhine into Germany – and large numbers of rocket-propelled V2 missiles would have been raining down on southern England, wreaking havoc at the ports and airfields tasked to support the invading troops.

In the actual course of events, it took the Allied armies a year to fight their way from the French coast to Berlin; but in a scenario in which the invasion was delayed, giving Hitler more time to prepare his defences, the struggle to reach Berlin might have taken twice as long.

At a conservative estimate, each year of the fighting in Europe brought on average about seven million deaths, so the significance of Turing’s contribution can be roughly quantified in terms of the number of additional lives that might have been lost if he had not achieved what he did.

If U-boat Enigma had not been broken, and the war had continued for another two to three years, a further 14 to 21 million people might have been killed.

Of course, even in a counterfactual scenario in which Turing was not able to break U-boat Enigma, the war might still have ended in 1945 because of some other occurrence, also contrary-to-fact, such as the dropping of a nuclear weapon on Berlin. Nevertheless, these colossal numbers of lives do convey a sense of the magnitude of Turing’s contribution.

Astonishingly, Turing’s wartime effort was perhaps not even his most influential contribution to modern civilisation, and was certainly not his first. When he was at Cambridge, in 1936, Turing tackled a famous, and unresolved, mathematics challenge known as the “decision problem”. In resolving the problem, Turing proposed a universal machine that could decide whether any given mathematical problem was provable or not.

In the universal machine, Turing introduced the idea of the stored programme computer years before such machines existed. Over a decade later, electronic technology had become sufficiently advanced to allow Turing’s ideas to make the leap from his brilliant mind into the real world. Although no one person can claim to have invented the computer, the descendants of Turing’s theoretical machine sit in billions of offices, homes and pockets around the world.

The maths of life

During his short academic career, Turing made towering contributions to a diverse range of areas, from pure mathematics to the theory of artificial intelligence. In 1952, aged 40, Turing wrote a lesser-known paper in a new area, which was no less brilliant than his preceding work. In The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, Turing proposed a mechanism by which patterns might form in the early embryo known as “diffusion-driven instability”.

The same mechanism, he realised, might account for a multitude of patterns in nature including those seen on animal coats, suggesting a mechanism for how the leopard got its spots. In particular, Turing’s theory predicts that animals can have spotty bodies and stripy tails, but not the other way around, a prediction that is borne out in many species of animals.

Turing’s idea of using mathematics to untangle the secrets of life were highly influential in the development of the relatively new field of science called “mathematical biology”. At the heart of this rapidly growing subject is the attempt to represent biological systems of interest mathematically or computationally using models.

Today, Turing’s legacy – the idea of taking a quantitative approach to biology – is helping to unravel some of life’s most enigmatic mysteries. Mathematical biologists are attempting to understand how things can go wrong during the development of an embryo and to suggest the best way to tackle outbreaks of deadly diseases like Ebola.

A gross injustice

In 1951, Turing was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. This honour is conferred on only the most eminent scientists. With it came recognition and respect from wider society, with no hint of the distress and humiliation this same society would inflict upon him the following year.

Turing was a gay man in a time when, in the UK, it was illegal to be gay. In 1952, he was charged with “gross indecency”. At his trial, Turing pleaded guilty, insisting that he saw nothing wrong with his actions. He was duly convicted and offered the choice between prison or probation with a course of the hormone stilboestrol for a year: a so-called “chemical castration”.

The “treatment” was designed to reduce libido and had the effect of rendering Turing impotent and causing him to grow breasts. If this were not humiliation enough, his conviction also meant that Turing’s security clearance was revoked. As a consequence, he was barred from continuing his ongoing consultancy work for Government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ) that had grown from his war-time codebreaking successes. Before his trial Turing had been asked to help crack the Soviet Union’s codes.

On June 7, 1954, Turing died of cyanide poisoning. Next to his bed lay a half-eaten apple. It was speculated (since Snow White was one of Turing’s favourite fairy tales) that he had laced the fruit with cyanide before consuming his own “poisoned apple”.

The remains of an apple were found next to the body, though no apple parts were found in his stomach. The autopsy reported that “four ounces of fluid which smelled strongly of bitter almonds, as does a solution of cyanide” was found in the stomach. Trace smell of bitter almonds was also reported in vital organs. The autopsy concluded that the cause of death was asphyxia due to cyanide poisoning and ruled a suicide.

In a June 2012 BBC article, philosophy professor and Turing expert Jack Copeland argued that Turing’s death may have been an accident: The apple was never tested for cyanide, nothing in the accounts of Turing’s last days suggested he was suicidal and Turing had cyanide in his house for chemical experiments he conducted in his spare room.

Alan Turing, World War II’s Greatest Hero

WHEN ALAN TURING DIED IN 1954, a modest obituary in the Manchester Guardian spoke of an academic who pioneered the creation of the new electronic calculating machines. He liked long-distance running, chess and gardening, and entertained the idea that “electrical computators” would one day “do something akin to thinking.”.

Shortly after World War II, Alan Turing was awarded an Order of the British Empire for his work. For what would have been his 86th birthday, Turing biographer Andrew Hodges unveiled an official English Heritage blue plaque at his childhood home. In June 2007, a life-size statue of Turing was unveiled at Bletchley Park. A bronze statue of Turing was unveiled at the University of Surrey on October 28, 2004, to mark the 50th anniversary of his death. Additionally, the Princeton University Alumni Weekly named Turing the second most significant alumnus in the history of the school – James Madison (an ex US president) held the number 1 position.

Turing was honoured in a number of other ways, particularly in the city of Manchester, where he worked toward the end of his life. In 1999, Time magazine named him one of its “100 Most Important People of the 20th century,” saying, “The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine.” Turing was also ranked 21st on the BBC nationwide poll of the “100 Greatest Britons” in 2002. By and large, Turing has been recognised for his impact on computer science, with many crediting him as the “founder” of the field.

Following a public petition, then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown released a statement on September 10, 2009 on behalf of the British government, which posthumously apologised to Turing for prosecuting him as a homosexual. “Thousands of people have come together to demand justice for Alan Turing and recognition of the appalling way he was treated,” Brown wrote in the statement. “While Turing was dealt with under the law of the time and we can’t put the clock back, his treatment was of course utterly unfair and I am pleased to have the chance to say how deeply sorry I and we all are for what happened to him.

“This recognition of Alan’s status as one of Britain’s most famous victims of homophobia is another step towards equality and long overdue. But even more than that, Alan deserves recognition for his contribution to humankind,” Brown stated. “It is thanks to men and women who were totally committed to fighting fascism, people like Alan Turing, that the horrors of the Holocaust and of total war are part of Europe’s history and not Europe’s present. So on behalf of the British government, and all those who live freely thanks to Alan’s work I am very proud to say: we’re sorry, you deserved so much better.”

In 2013, the Queen posthumously granted Turing a rare royal pardon almost 60 years after he committed suicide. Three years later, on October 20, 2016, the British government announced “Turing’s Law” to posthumously pardon thousands of gay and bisexual men who were convicted for homosexual acts when it was considered a crime. The law also automatically pardons living people who were “convicted of historical sexual offences who would be innocent of any crime today.

Ian says:

Biography and ‘The Imitation Game’ film

In 1983 Turing’s acclaimed biography by Andrew Hodges, “Alan Turing: The Enigma” was published. This book provides a (very) loose inspiration for the 2014 movie, “The Imitation Game”, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley.

The film is entertaining but quite a lot of the script is simply made up, which is a pity because when I watched it, I naturally believed it’s story only to find out later just how inaccurately it reflected actual events. Turing’s unusual life and remarkable achievements were presumably considered too complex or insufficiently interesting or too embroiled in homophobia to fill two film hours accurately so the filmmakers simply invented a subplot in which Turing discovers the identity of a Soviet agent working at Bletchley Park but is blackmailed into keeping quiet. That is, they falsely portrayed him as a traitor and explicitly linked it to his homosexuality. Cumberbatch also depicts Turing as a ‘typical’ autistic, probably having Aspergers syndrome, extending Dustin Hoffman’s ‘Rain Man’ image, probably because Turing was an eccentric mathematics genius. Turing is portrayed as someone who struggles with ordinary human interaction, is literal-minded to a fault and incapable of understanding jokes. Although Turing himself may indeed have had some of the traits of Asperger syndrome Cumberbatch’s portrayal is nothing like the real Alan Turing, apparently, who was warm, charming and funny and there is little or no real evidence that supports this depiction, quite the opposite, in fact.

Bletchley Park today

For three decades after the war Britain’s draconian Official Secrets Act erased the history and silenced the participants so very few others knew anything about Bletchley Park, Turing’s role or indeed almost anything about anything that went on there between 1938 and 1946. Almost immediately after the war the site was cleared, the decoding machines were dismantled and GC&CS moved to RAF Eastcote in Middlesex and was renamed GCHQ. Thereafter, the estate became a teacher training school and a management training centre for the Post Office. In 1991, there were plans to demolish it for a housing development but the Bletchley Park Trust was established and bought the site. Churchill famously called the BP workers the geese who “laid the golden eggs and never cackled.” So when the Trust opened a museum there in 1993, the point was to show off some golden eggs, and perhaps even cackle a bit.

Visiting Bletchley Park

The museum was also tapping into the growing interest in Alan Turing: the brilliant mathematician, master code breaker and irascible, persecuted genius.

The exhibitions strike a sober and weighty note, though with some flaws: They are splintered among many buildings; there is no systematic narrative; older exhibitions mix with the new. The effect is a little like that of the mansion, where rooms were added in different eras and with different styles. But, in the end, it doesn’t matter: There is more here than can be absorbed in a single visit.

One exhibition sketches the daily life of this secluded wartime world, with its high concentrations of women, as well as other eccentric geniuses.

Displays of German coding machines show just how daunting a task the code breakers faced: Those machines contained rotating discs and a plug board that, on the German Navy’s Enigma, for example, allowed for about a billion million million possibilities — and settings were changed every day.

Displays of German coding machines show just how daunting a task the code breakers faced: Those machines contained rotating discs and a plug board that, on the German Navy’s Enigma, for example, allowed for about a billion million million possibilities — and settings were changed every day.In the huts, sound and video installations evoke the frantic yet meticulous work that went on. Turing’s office, in Hut 8, looks as if he had just stepped out, his cryptic markings covering a blackboard. Desks throughout the complex, like his, are covered with pencils, pads, typewriters and reference volumes — state of the era’s cryptographic art. Nearby are higher-tech touch screens that guide us through some techniques that were used.

These exhibitions are likely to grow in importance over time, because they are so detailed and careful — good correctives for growing misconceptions. For example, the most common image now associated with Bletchley Park is of the Bombe, a magnificent machine whose clicking rotors are also often used in “The Imitation Game” as evidence of Turing’s genius. The Bombes were all dismantled after the war, but in 2007, a working model was recreated that now hypnotically draws visitors to a demonstration.

But however impressive, the Bombe is, so to speak, overblown. It is not, the exhibition reminds us, a computer. It does no calculations. It simply runs through possible Enigma settings. Polish cryptographers had built a simpler one before the war. The Bombe was necessary, but insufficient.

The real advances in computer technology occurred in a room-size monstrosity with over 1,500 vacuum tubes, built by an engineer, Tommy Flowers, and known as the Colossus. It may have been the world’s first programmable electronic computer, and was used to break another notoriously complex code, one used by Hitler and the German high command. It, too, was demolished, but a working reconstruction is the centrepiece of the independently run National Museum of Computing, located in space rented from Bletchley Park (and well worth visiting).

In many ways, too, the human decoding work was more impressive than the mechanical. Each day, the task was to determine the Enigma settings that were used. Possibilities had to be narrowed by statistical analysis and clever deductions before the Bombe could be used. And that was where Turing and his colleagues showed their brilliance.

A touch screen here gives a particularly elegant example. Every time a letter was encoded by an Enigma machine, the Enigma’s rotors would advance, changing the code settings for the following letter. So identical letters would rarely have identical codings, even within the same message. But the Enigma also had a crucial quirk: A letter could never be encoded as itself. (A W in code was never a W in the original.)

One day, a German dispatch seemed peculiar to Mavis Batey, one of Bletchley’s leading code breakers: It did not contain a single L. Batey guessed that it was a test message, that the operator, feeling lazy, sent it off by just hitting a single letter over and over. So this message was entirely composed of the one letter the coded text did not contain: L. This led her to the day’s Enigma setting. And that setting decoded other messages that led to the British Navy’s victory in the 1941 Battle of Matapan, in Italy.

Ian says:

The day we visited, on a bright Monday in early November, the Park was not very busy, as we expected. There were many school parties visiting with us, which was good to see, but many seemed too young to understand the activities that went on at Bletchley let alone appreciate the impact these activities had on the progress of the war. As the review above notes, we found different exhibitions in each of the huts that you could visit in any order. When we thought we’d visited them all I realised, but only because I knew Turing worked in hut 8, that we’d not visited hut 8 so I went back to ‘find’ it and found it one of the most interesting parts of the museum. It was great to stand in Alan Turing’s (recreated) office, which indeed feels like he just stepped out. Unfortunately, the block containing the Alan Turing exhibition was closed for two months for refurbishment so we couldn’t visit one of the most anticipated parts of our tour and neither could we visit the History of Computing containing the working Bombe and the Colossus computer, used to decipher the Lorenz codes, because it’s only open on certain days of the week. Entry is quite expensive but the tickets are valid for a year so we’ll have to go back.

Overall, it was good to walk in the footsteps of the people who worked there and so helped the war effort but knowing it is all a recreation does rob it of its romance a little, adding to the disappointment of not being able to visit all the exhibits. I wondered what success the Axis Powers had decoding Allied signals (quite a lot, I later found out, but not as comprehensively) but there didn’t seem to be anyone available to ask.

The wonder to me is, as Turing died aged 41, just what else would he have achieved if he had lived a full life?

Churchill said in a 1940 speech following the heroic success of the Battle of Britain pilots, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.“. If, after the war, Churchill had been able to talk about Turing and the help he and his codebreaking Bletchley Park colleagues provided to the Allies, I wonder whether he would have added them to that sentiment.

Turing’s brilliant work during the war saved countless actual thousands and potentially millions of lives. His work in mathematics and logic laid out the blueprint for modern computers and, in turn, the digital age. To honour his trailblazing contribution, the Turing Prize — considered the Nobel Prize of computing — was established in 1966 as the field’s highest distinction.

Innovative, forward thinking and brave in the face of prejudice, Alan Turing was an enigma in his own time.

Turing went on to personally break the more advanced four-rotor naval Enigma code used by the U-boats preying on the North Atlantic merchant convoys. It was a crucial contribution. The convoys set out from North America loaded with vast cargoes of essential supplies and troops for Britain, but the U-boats’ torpedoes were sinking so many of the ships that Churchill’s analysts said Britain would soon be starving.

Turing went on to personally break the more advanced four-rotor naval Enigma code used by the U-boats preying on the North Atlantic merchant convoys. It was a crucial contribution. The convoys set out from North America loaded with vast cargoes of essential supplies and troops for Britain, but the U-boats’ torpedoes were sinking so many of the ships that Churchill’s analysts said Britain would soon be starving.

Displays of German coding machines show just how daunting a task the code breakers faced: Those machines contained rotating discs and a plug board that, on the German Navy’s Enigma, for example, allowed for about a billion million million possibilities — and settings were changed every day.

Displays of German coding machines show just how daunting a task the code breakers faced: Those machines contained rotating discs and a plug board that, on the German Navy’s Enigma, for example, allowed for about a billion million million possibilities — and settings were changed every day.