Generally regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’ is a 1957 epic war film directed by David Lean, based on a 1952 novel written by Pierre Boulle. It stars Alec Guinness, William Holden and Jack Hawkins, three of the most famous Hollywood actors of the time. The film won seven Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director (Lean), Best Actor (Guinness as Colonel Nicholson, British commander) and Best Supporting Actor (Sessue Hayakawa as Colonel Saito, Japanese commander).

To be honest I have grown up believing the film was a reasonable depiction of a true incident of the war in “the Far East” and the Bridge’s wartime history. In fact Boulle’s novel and the film’s screenplay are almost entirely fictional, we have learned. A little research whilst we have been here and visits to the two Memorial Museums and the beautifully-tended Commonwealth War Graves cemetery showed how ill-informed I have been all my life. So this trip was not just a remarkable travel experience but a sobering educational visit for both of us too.

The first shock/surprise/revelation was learning how many lives were lost building the railway, over 100,000. More than twenty percent of all POWs who worked on the railway died. The living and working conditions on the Burma Railway were often described as “horrific”, with maltreatment, sickness and starvation. The estimated number of civilian labourers and POWs who died varies considerably but the Australian Government figures suggest that of the 330,000 people who worked on the line (including 250,000 Asian labourers and 61,000 Allied POWs) about 90,000 of the labourers and about 16,000 Allied prisoners died, including nearly 7,000 British POWs. Conditions suffered by the POWs under the Japanese were much worse than (could be) depicted in the film. Too much detail would be inappropriate in a ‘Postcard from….’ but by way of example, we learned men in hospital were denied rations that were already insufficient and poor quality, as ‘encouragement’ for them to get back to work. The construction of the Burma Railway is counted as a war crime committed by Japan.

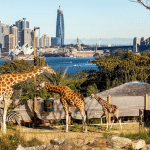

The second shock was seeing the Bridge itself. The very substantial wooden bridge in the film was destroyed by Col. Nicholson falling on the detonator at the climax of the film. OK, I knew that to be Hollywood dramatisation but I had no idea there were actually two bridges on/over the River Kwae. A wooden railroad bridge over the Khwae Yai was finished in February 1943, but it was a far less substantial bridge than the one depicted in the film. This bridge was soon accompanied by a more modern steel and concrete bridge in June 1943, made of eleven curved-truss bridge spans which its Japanese builders brought from Java in the Dutch East Indies. This is the bridge that remains today. The wooden bridge was used as a backup rail route in case the main bridge was damaged by Allied bombing. It was otherwise used for pedestrians and cars. No trace of this wooden bridge remains today. The two bridges were just hundreds of meters apart, near to the current war cemeteries and museums in the city of Kanchanaburi, Thailand.

The ‘real’ Bridge on the River Kwai is much smaller than I was expecting because I had in my mind the huge wooden bridge like the Fourth Road Bridge design in the film. Indeed why would it need to be any larger than it is for a single track railway? A smaller bridge is also a smaller target from bombing. The Col. Nicholson-built bridge in the film was actually constructed in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, and was Hollywood-impressive big enough to take two trains unnecessarily side-by-side. The two bridges were successfully bombed and damaged on 13 February 1945 by RAF bomber aircraft. Repairs were carried out by POW forced labour and by April the wooden trestle bridge was back in operation. On 3 April, a second bombing raid, this time by heavy bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces, damaged the rail bridges once again. Repair work soon made both bridges operational again by the end of May. A second RAF air-raid on 24 June finally severely damaged and destroyed both bridges and put the entire railway line out of commission for the rest of the war.

The third surprise was a better one. The film depicted Col. Nicholson as a Japanese appeaser, at least until the very end of the film when he cries, “What have I done?”. Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey of the British Army was the real senior Allied officer at the bridge. Toosey was very different from Nicholson and was certainly not a collaborator who felt obliged to work with the Japanese. Toosey strove to delay construction. While Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged it: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures and the concrete was badly mixed. Some consider the film to be an insulting parody of Toosey.

A Death Railway study noted, “What makes this [railway] an engineering feat is the totality of it, the accumulation of factors. The total length of miles, the total number of bridges – over 600, including six to eight long-span bridges – the total number of people who were involved (a third of a million), the very short time in which they managed to accomplish it, and the extreme conditions they accomplished it under. They had very little transportation to get stuff to and from the workers, they had almost no medication, they couldn’t get food let alone materials, they had no tools to work with except for basic things like spades and hammers and they worked in extremely difficult conditions – in the jungle with its heat and humidity. All of that makes this railway an extraordinary accomplishment.”

The Japanese Army transported 500,000 tonnes of freight over the railway before it fell into Allied hands. It was in use for only twenty months.

We then went on to walk through Hellfire Pass, a particularly difficult section of the line to build: it was the largest rock cutting on the railway, in a remote area and the POWs and workers again lacked proper construction tools. The mainly Australian POW workers but also British, Dutch and other Allied prisoners of war, along with Chinese, Malay and Tamil labourers, were forced by the Japanese to complete the cutting. Sixty-nine men were beaten to death by Japanese guards in the twelve weeks it took to build the cutting and many more died from cholera, dysentery, starvation, and exhaustion.

The next day we rode the Death Railway itself for nearly an hour. We passed very slowly over the POW-built viaduct that still carries the railway today.

In case you’re interested here is a link to my Kanchanaburi Google photos album: photos.app.goo.gl/TanpH9ZdrzkHdy4t9

Wish you were here. 🙋🏼♂️🙋♀️