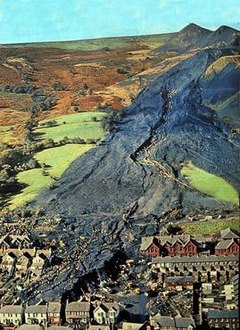

The Aberfan Disaster was the single most appalling and shocking tragedy in modern Welsh history

Aberfan in the days immediately after the disaster, showing the extent of the spoil slip. October 1966

published the results of their academic study of the Aberfan disaster and its repercussions; their work included government papers released in 1997 under the thirty-year rule. Their opinion is that “the Coal Board ‘spin-doctored’ its way out of trouble, controlling the public agenda from the day of the disaster until the tips were finally removed.”. I noticed that their book, ‘Aberfan, Government and Disasters’ was out of print but an updated version was due to be published at the end of March. Having waited this long I felt I could wait another few weeks to read the full story but when I went back onto Amazon to buy it in April, I frustratingly found it was ‘unavailable’ and not available electronically either. So I bought an old library copy of their original 2000 book and learned that the detailed story, properly researched, is both fascinating and more than a little depressing.

published the results of their academic study of the Aberfan disaster and its repercussions; their work included government papers released in 1997 under the thirty-year rule. Their opinion is that “the Coal Board ‘spin-doctored’ its way out of trouble, controlling the public agenda from the day of the disaster until the tips were finally removed.”. I noticed that their book, ‘Aberfan, Government and Disasters’ was out of print but an updated version was due to be published at the end of March. Having waited this long I felt I could wait another few weeks to read the full story but when I went back onto Amazon to buy it in April, I frustratingly found it was ‘unavailable’ and not available electronically either. So I bought an old library copy of their original 2000 book and learned that the detailed story, properly researched, is both fascinating and more than a little depressing.Essentially, the Aberfan miners and their families were repeatedly failed, not just by those charged and paid to ensure their safety but by almost everyone involved in the events of the years thereafter. McLean & Johnes find it hard to identify more than a small handful of players that did acquit themselves as we might, nowadays, expect.

Aberfan Disaster Tribunal

On 25 October 1966, four days after the disaster and after resolutions in both Houses of Parliament, the Secretary of State for Wales formally appointed a tribunal to inquire into the disaster, chaired by the respected Welsh judge and Privy Councillor Lord Justice Edmund Davies, who was born two miles from Aberfan. The inquiry had an initial public meeting on 2 November 1966 and took evidence in public for 76 days, spread over the next five months during which time 136 witnesses testified. The tribunal report thought “much of the time of the Tribunal could have been saved if … the National Coal Board had not stubbornly resisted every attempt to lay the blame where it so clearly must rest – at their door”.

The tribunal concluded its hearings on 28 April 1967 and published its report on 3 August. Among their findings was that “[b]lame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board. … This blame is shared (though in varying degrees) among the National Coal Board headquarters, the South Western Divisional Board, and certain individuals.” They added that the “legal liability of the National Coal Board to pay compensation for the personal injuries (fatal or otherwise) and damage to property is incontestable and uncontested”. In its introduction the inquiry team wrote that it was their:

“… strong and unanimous view … that the Aberfan disaster could and should have been prevented. … the Report which follows tells not of wickedness but of ignorance, ineptitude and a failure in communications. Ignorance on the part of those charged at all levels with the siting, control and daily management of tips; bungling ineptitude on the part of those who had the duty of supervising and directing them; and failure on the part of those having knowledge of the factors which affect tip safety to communicate that knowledge and to see that it was applied.”

Strong words, but Shipton suggests the Tribunal was, in fact, wrong to conclude the NCB failures were due to ignorance and ineptitude as his and McLeod & Johnes’ research had uncovered evidence that the NCB had recent experience of tip failures, contrary to the NCB assertions to the Tribunal. In fact, Shipton highlights that the NCB’s most recent tip failure experiences were not shared with the Tribunal, but he stops short of calling that wickedness.

Nine employees of the NCB were censured by the inquiry, with “many degrees of blameworthiness, from very slight to grave”, although McLean and Johnes consider that some senior staff whom the evidence shows to have been culpable were omitted, and one junior member of staff named in the report should not have been blamed.

HM Inspectorate of Mines

McLean and Johnes observed that HM Inspectorate of Mines went largely unchallenged by the tribunal, although they contend that the organisation failed in their duty; in doing so, they created a situation of ‘regulatory capture’, where rather than protecting the public interest – in this case the citizens of Aberfan – their regulatory failures fell in line with the interests of the NCB, the organisation they were supposed to be overseeing. It is clear that the spoil tips, evident to everyone, were largely ignored as a part of the mine’s safety operations by just about everyone who should have been concerned. In fact, the disaster itself was not a statutorily reportable mining incident because no colliery workers were killed or injured.

Mine spoil was only tipped on steep valley sides in the South Wales coalfields. They were therefore a unique and foreseeable issue by both the Inspectorate and the NCB but both failed the people of Aberfan.

National Coal Board

The NCB as an organisation was not prosecuted and no NCB staff were demoted, sacked or prosecuted as a consequence of the Aberfan disaster or for evidence given to the inquiry. During a parliamentary debate on the disaster, Margaret Thatcher, then the opposition spokesman on power, raised the situation of one witness, criticised by the inquiry, who had subsequently been promoted to a board-level position at the NCB by the time the report was published.

Initially the NCB offered bereaved families £50 in compensation but this was raised to £500 for each bereaved family, little more than one might expect for a killed animal. The NCB called the amount “a good offer”. Many families, not unreasonably, thought the figure inadequate and petitioned for an increase but to no avail.

Disaster fund & Charity Commission

The fund set up by the mayor of Merthyr Tydfil on the day of the disaster grew rapidly and within a few months nearly 88,000 contributions had been received from all over the world; the final total raised was £1.75 million. In 1967 the Charity Commission advised that any money paid to the parents of bereaved families would be against the terms of the Disaster Fund trust deed. After arguments from lawyers for the trust they agreed that there was an “unprecedented emotional state” surrounding Aberfan and suggested that sums of no more than £500 should be paid. Members of the trust told the commission that £5,000 was to be paid to each family. The Commission agreed that the amount was permissible but stated that each case should be examined before payment “to ascertain whether the parents had been close to their children and were thus likely to be suffering mentally”. In November 1967 the Commission threatened to remove trustees of the disaster fund or make a financial order against them if they made grants to parents of children who were physically uninjured but who were suffering mentally—some surviving children complained of being afraid of the dark and loud noises, while some refused to sleep alone; the Commission informed them that any payments would be “quite illegal”. The decision affected 340 physically uninjured children.

McLean and Johnes consider that “the Commission protected neither donors nor beneficiaries. It was caught between upholding an outdated and inflexible law … and fulfilling the varied expectations of donors, beneficiaries and the fund’s management committee”. It also seems, from the examples above, that the fund should not have been converted into a charity regulated by such an unsuitable and unreasonable regulator but who was to know that at the time. If the fund had not been designated a charity then fund payments would have (rather incredibly) been taxable.

The Disaster Fund funded the building of a community centre in the village and a memorial garden, which was opened by the Queen in March 1973. In 1988 the Aberfan Disaster Fund was separated into two entities: the Aberfan Memorial Charity and the Aberfan Disaster Fund and Centre. The Aberfan Memorial Charity oversees the upkeep of the memorial garden and Bryntaf Cemetery, and the Disaster Fund provides financial assistance to “all those who have suffered as a result of the Aberfan Disaster by making grants of money or providing or paying for items, services or facilities calculated to reduce the need, hardship or distress of such persons”.

The Disaster Fund also paid for the demolition and rebuilding of the village’s Bethania Chapel, used as a temporary mortuary where victims were taken to be identified by relatives. The villagers said it was impossible to continue to use the building as a church afterwards and they appealed to the NCB to replace it but Robens refused. The chapel was demolished in 1967 and a new chapel was erected in 1970.

Removal of the tips

The residents of Aberfan petitioned George Thomas, who had become Secretary of State for Wales in April 1968, for the tips above the village to be removed. Thomas later stated the tips “constitute a psychological, emotional danger” to the people of Aberfan. The NCB had received a range of estimated costs for removing the tips from £1.014 million to £3.4 million. Lord Robens, NCB chairman, informed The Treasury that the cost would be £3 million and that the NCB would not (or could not afford to) pay for the removal and between November 1967 and August the following year he lobbied to avoid having the NCB pay. The Chief Secretary to the Treasury also refused to pay and said that the costs were too high. But the government was persuaded they had to be removed and to pay for their removal £150,000 was taken from the disaster fund – lowered from an initial £250,000 first requested. The NCB paid £350,000 and the government provided the balance, with the proviso it was only up to £1million. George Thomas, (later Speaker of the Commons who became famous for his cries of “Order! Order!” in his broad Welsh accent when the House of Commons was first broadcast on BBC Radio), inexplicably thought the deal to be fair as the monies taken represented ‘only the interest earned from the Fund, not the capital”. The final cost of removing the tips was £850,000. The fund trustees voted to accept the request for payment after realising that there was no alternative if they wanted the tips removed. S. O. Davies, the local MP and the only member of the committee to vote against the payment, resigned in protest. There was a reminder of the danger from the tips for the residents of Aberfan when, in August 1968, heavy rain caused slurry to be washed down the village’s streets. At the time, the Charity Commission made no objection to this action but later the political scientists Jacint Jordana and David Levi-Faur considered the payment “unquestionably unlawful” under charity law. It’s not clear (to me) whether the Charity Commission did or did not provide advice on whether Fund monies being used in this way was illegal or not but it doesn’t seem that, if they did think it illegal, they did anything about it so I’ll assume there’s either a piece of this story missing, e.g. the Commission were told to keep quiet, maybe the they were somehow unaware of the transaction or maybe they were simply negligent.

Legacy payments

Merthyr Vale Colliery closed in 1989. In 1997 Ron Davies, the Secretary of State for Wales in the incoming Labour government, repaid to the disaster fund the £150,000 that it had been induced to contribute towards the cost of tip removal. Davies made no allowance for inflation or the interest that would have been earned over the intervening period which would have been £1.5 million in 1997. The payment was made in part after Iain McLean’s examination of the papers released by the government. I’ve not found any explanation yet why Davies only repayed the sum originally taken nearly 30 years before because he would have known £150,000 wouldn’t properly compensate the Fund. Presumably it was a token to recognise the Labour government at the time had been wrong. It was only in February 2007 that the Welsh Government announced a donation of £1.5 million to the Aberfan Memorial Charity and £500,000 to the Aberfan Education Charity, which represented an inflation-adjusted amount of the money taken.

Merthyr Tydfil Borough Council

MTBC was overwhelmed in the weeks and months following the disaster and it proved too small an authority to cope with the additional demands required of it. From my reading it doesn’t seem that it received any extra funding to cope with the additional demands on its services and McLean/Johnes note the very long additional hours that many Council staff worked to try to cope. Remarkably, it was also unable to get the NCB to act on tip failure warnings made by the Borough and Waterworks Engineer, DCW Jones, to the NCB’s Area Chief Mechanical Engineer. The risk to Pantglas school of a tip slippage was actually acknowledged by the NCB engineer but the NCB did nothing, presumably either due to complacency following their previous tip slip experiences, or that they were unable to find a suitable alternative tip location, or maybe they were simply negligent. Quite why MTBC didn’t turn to the courts for support I don’t know but this is a point I shall return to later. To underscore the MTBC’s difficulties McLean & Johnes note that the NCB still hadn’t paid it compensation for destroying Pantglas school nearly four years later. Again, the proper recourse might have been the courts or pressure from a properly-placed word to the national Press.

Lord ‘Alf’ Robens

Professor McLean does not mince words in his condemnation of Lord Robens: “[A] Heartless bully who added to [the] agony of Aberfan: Thirty years on, documents reveal how Coal Board chief Lord Robens dodged the blame for the disaster“. The Observer, 5 January, 1997.

The ‘villain of the piece’ throughout the aftermath was Alf Robens, the NCB chairman, clearly a formidable politician in his own right. Having been heavily criticised by the Davies Tribunal one might have expected Robens to have been somewhat contrite thereafter but not a bit of it. He knew the government (both Labour and later, Conservative) needed his and the NCB’s continued help to reduce the size of the loss-making coal industry without provoking a national strike and he used this knowledge to safeguard his own position.

Various stories abound about his behaviour including his decision not to visit Aberfan until after he had been installed as the first Chancellor of the new Surrey University, an investiture which was due to take place that evening. For a man who had left school at 15 I can imagine such an honour would have been important to him but he must surely have forseen the expected reaction of both the University and the public when his actions were, inevitably, disclosed. The NCB even tried to cover for him by telling the Secretary of State that Robens was directing rescue operations from Aberfan. I don’t believe this is a particularly significant issue because the NCB’s director of production went to Aberfan straight away but it’s indicative of his thinking and values.

Robens’ Wikipedia entry contains the following text:

“Speaking to the media after he arrived in Aberfan on the Sunday after the disaster, Robens was concerned that the initial shock and sorrow might give way to anger, possibly directed towards the men who worked at the top of the spoil heaps. To avoid this he said that those men could not have foreseen what happened. A TV interview during which he made that comment proved to be unacceptable for broadcasting due to the atmospheric conditions and instead the interviewer broadcast a paraphrase of the interview which wrongly made it seem that Robens had claimed that no one in the NCB could have foreseen it. This was later taken by the Aberfan enquiry to imply that the Board were contesting liability notwithstanding the 19th Century case of Rylands v Fletcher which meant that they had absolute liability for damage caused by a ‘dangerous escape’ of material. It is true that in a later interview Robens claimed that the disaster had been caused by “natural unknown springs” beneath the tip, but evidence emerged that the existence of these springs was common knowledge.

The report of the Davies Tribunal which inquired into the disaster was highly critical of the NCB and Robens. [Robens] had, however, proposed to appear at the outset of the enquiry to admit the NCB’s full responsibility for the disaster but the Chairman of the Tribunal [Lord Davies] advised him that this would not be necessary. Robens should have ignored this advice and insisted on appearing. In the event, when it was clear that his earlier comments to reporters had been misinterpreted at the Tribunal as a denial of responsibility he offered to appear at the enquiry to set the matter straight. He conceded that the NCB was at fault, an admission which would have rendered much of the inquiry unnecessary had it been made at the outset notwithstanding the advice of Lord Edmund Davies that his appearance was not necessary.”

I find this Wikipedia entry too incredible to believe. The idea that Lord Davies would have advised the NCB chairman that his presence and admission of fault on behalf of the NCB would be unnecessary when the Inquiry report later specifically criticised him and the NCB for avoiding such behaviour almost makes me believe the Robens’ entry was written after the event by the NCB themselves.

But the biggest scandal of the aftermath story is the pressuring of the Disaster Fund trustees to help pay for the removal of the NCB’s tips above the village. McLean notes that Robens refused to pay for them to be removed, he lied to the Treasury how much it would cost (£3M) and asserted there was no good economic reason for their removal because his engineers noted they were safe(!). (A contractor offered to remove them for £800,000 if they could also sell the coal they reclaimed from it but the government were advised to decline the proposal because the coal sold would undercut the NCB’s coal price.)

A rather different story is again noted in Robens’ Wikipedia entry:

“In the wake of the disaster Robens was asked that the NCB should fund the removal of the remaining tips from Aberfan. He was, however, advised that the cost of doing so would have obliged the NCB to exceed their borrowing limits set by the Government. To incur that cost would in effect have broken the law. It was not that Robens refused to pay.”

There seem to be a number of ways to spin this part of the story but it seems to me that whoever paid for the tips to be removed it shouldn’t have been the Disaster Fund. There is discussion that part of the final cost was met by the Disaster fund, part by the NCB and part by the Government (both essentially the same thing for a nationalised industry) but the differentiation is important as it allows part of the removal cost to be allocated elsewhere. There seems to have been no idea at the time that the cost of removal of the tips was part of the cost of coal, no matter what Government spending limits were or who actually paid for their removal at the time. There was a full understanding that coal mining was in decline and not many pits were profitable so avoiding any additional costs was important, but surely not when a disaster had claimed so many lives and the nationalised industry itself was clearly to blame. Nevertheless, whilst this ‘explanation’ does help me understand a little of what might have been driving Robens’ thinking I remain uncomfortable that one man, Robens, seemed to wield so much seemingly-unchecked arbitrary decision-making power (much as President Donald Trump seems able to do in US politics today).

George Thomas

The final character I should consider is Viscount Tonypandy, George ‘Mr Speaker’ Thomas, then Welsh Secretary, and the person identified by McLean & Johnes being most responsible for the disaster fund paying part of the cost for Aberfan tips to be removed. It is remarkable, to me, that although ‘the Government’ was persuaded that the NCB’s tips should be removed, it (who?) looked for others to pay for it. Thomas himself clearly thought that using Fund monies was wrong in principle because in his memoirs he notes that he was not looking forward to discussing it with the Trustees. He wrote that he was pleased when they agreed to the payment but surely he realised the Trustees felt they had to agree to help pay or the tips wouldn’t be removed? Thomas wouldn’t, apparently, have recognised his actions would later be viewed as improper but he was indeed heavily criticised after his death, even resulting in a local pub named after him, the Lord Tonypandy, having to change its name following pressure from locals.

I tend to agree that Thomas wouldn’t have thought his actions to be so wrong at the time because there seemed to be no reasonable alternative for funding the tips removal. But quite why he or ‘the Government’ thought that an arbitrary government spending limit meant the relatively small amount of £150,000 needed to be taken from the Fund and this was thought worth the public’s wrath is very hard to understand today. Thomas could surely, with support from the local MP, S O Davies, have pressed the argument more forcibly with Harold Wilson, the prime minister.

Learnings

Mining in South Wales and elsewhere was a truly filthy, hazardous, hot, physically demanding, claustrophobic, life-limiting, back-breaking job. Above ground, the tips of rock, shale and other mining debris were evidence of the labours below, scarring the valleys. Large lumps of coal were required for home heating so the washings and smaller residues were also tipped with the larger pieces of rock, shale and other debris. There was no concept of ‘polluter pays’ or ‘true cost of coal’ accountancy which would have included associated mining costs such as family compensation following the many mining deaths, health and early-death issues such as pneumoconiosis, safety and training costs, all Coal Board and marketing costs plus environment stabilisation and reinstatement costs when a pit was exhausted or closed. If there had been then there may have been more material to discuss with Parliament and the mineworker unions than holding to a ‘secret plan’ to run down the coal industry by stealth but, with no other work available and with so many valley people dependant on the pit for their livlihoods it was in everyone’s interests to keep quiet and maintain the status quo.

The National Coal Board (NCB) wielded god-like power. Since taking control of UK mining, nationalised in 1947, the NCB was revered as the salvation for a dwindling coal industry. It had a firm grip on central government and the Labour-entrenched local governments of South Wales via its employees and union officials who served as councillors. In the post-war corporatist climate of the 1960s, it was held in what now seems uncomfortable reverence. The working man knew his place; authority knew best.

Health and safety, counselling, accountability, litigation, compensation, awareness training – at times met with derision – are the tenets of our modern day, probably for good reason. At the time there was no knowledge of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2003 found that half the survivors of the disaster had experienced PTSD at some time in their lives, that they were more than three times more likely to have developed lifetime PTSD than a comparison group of individuals who had experienced other life-threatening traumas, and that 34 per cent of survivors who took part in the study reported that they still experienced bad dreams or difficulty sleeping because of intrusive thoughts about the disaster. McLean /Johnes note that they are unaware of any successful compensation claims by any survivor of the disaster.

McLean notes in a February 2007 article:

“Some of the causes of Aberfan were specific to the now-disappeared South Wales coalfield, and others were remedied by legislation. Only in South Wales were colliery tips dumped on slopes; all have now gone or been stabilised. The legislation under which Aberfan was not a notifiable accident (because no colliery workers were killed) was amended. A new framework for health and safety legislation was drawn up in 1972 by the Robens (yes, really!) Committee, and has remained in place ever since, under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. The 1974 act has generally been reckoned a success but Robens’s appointment to chair the committee that introduced it is beyond satire.

Other lessons remain. Here are ten of them; there are others.”

McLean’s full article is here: McLean: 10 Lessons from Aberfan: ‘No end of a lesson’

In their book, Aberfan: Government and Disaster, McLean & Johnes expand on the learnings from Aberfan and relate them to subsequent disasters such as Hillsborough, the Herald of Free Enterprise, Kings Cross, the Marchioness, Dunblane and others. They conclude that public policy became less attentive to producers and more towards consumers than was the case in 1966-70. (I would still like to read their update in the 2018 edition when it becomes available though!)

So, finally….

What I’m missing, in my interested layman’s review of the Aberfan tragedy aftermath, is a properly considered view by a respected social or legal historian who might help put the actions and events in proper context of the times. These were times when a mining widow would not be properly compensated for the death of her mining husband because she would not be expected to cope with such a vast sum of money or that it would improperly raise her social status. Instead she was given a weekly pension for herself and her children amounting to a few shillings per week. Authority was paternalistic and went largely unchallenged.

After the disaster victims were considered by the NCB to be troublemakers; they seem to have had no concept that the families should have been treated with respect and care. Instead the NCB seemed to treat them as threats to the mine, which maybe they were.

There seems to have been an almost simple, albeit at times angry, expectation by society of acceptance of the actions and decisions of various Government ministers and officials, including those of Robens, the Charity Commission, the Mines Inspectorate, the NCB and probably many others, without much argument in Parliament, the National Press or more properly perhaps, the courts. It is this final aspect, the seeming lack of involvement of the judiciary and the courts following the disaster, that I find so astonishing. I almost feel I must have missed an important chapter of the story I’ve been studying these past few weeks. I can’t imagine if, nowadays, a respected High Court judge, such as Lord Davies at the time, had clearly and unequivocally determined the responsibility for the disaster and to pay compensation lay with the NCB, that the courts would not have firmly upheld that judgement and ensured appropriate corresponding actions. Then, no amount of lobbying, behind-the-scenes Government dealmaking or other shenanigans by Robens, the Government or anyone else would have been successful, as it seems they were in the Aberfan aftermath.

Martin Johnes, who teaches history at Swansea University, says this in his own blog:

“In the face of the [Tribunal] report, it now seems surprising that nobody was prosecuted, dismissed, or demoted or even said sorry.

It is also surprising that Robens’ offer to resign as NCB chairman, which even at the time was seen as perfunctory, was rejected. Public records released under the thirty year rule, show that he had advance sight of the tribunal report and his private office ran a media campaign to keep himself in place. Through very public attacks on government fuel policy, he was able to portray himself as a defender of the industry and win the support of the unions. This was not a new line for him to take but Robens was a great PR manipulator and he knew that he was securing his position. Ministers let him stay, despite disliking him, because they thought he was the only man who could manage the decline of the coal industry and avoid strike action. In effect, Robens’ behaviour after Aberfan became irrelevant to whether he kept his job or not. Rather, political expediency was the name of the game.

Nobody suggested that Robens himself was to blame for the disaster but he was the head of the organisation that clearly was. The extent of mismanagement revealed by the Tribunal was such that the question of prosecution arose in Aberfan and the media. However the NCB itself avoided prosecution because the concept of corporate manslaughter was very much on the fringes of legal procedures. Mining was a dangerous industry where accidents were normalised as an almost inevitable part of operations. This is not to say that they were taken lightly but rather that they were seen as just that, accidents.

Accidents might be the product of individuals’ errors maybe but the idea that those errors could be fostered by a wider corporate culture that amounted to criminal negligence was simply not part of the contemporary agenda. When the question of manslaughter charges was raised it was with regard to individual employees not the NCB itself. Concepts of corporate responsibility, in and outside the coal industry, were essentially under developed. Thus, despite the evidence to the contrary, the Aberfan disaster did nothing to challenge the picture of disasters as tragic accidents rather than criminal negligence.

Before the disaster, the NCB’s economic and local political power meant no one, including the small local authority in Merthyr, was able to challenge it to do more about fears on tip safety. After the disaster, the NCB’s economic and national power meant its interests took precedent over those whose children it had killed.”

At the end of my journey through the Aberfan aftermath story I am left feeling that no-one nowadays would be content with many, indeed any, of the various decisions and actions taken in the aftermath of this tragedy and presumably, most people at the time wouldn’t have been either. I guess it was society’s post-war expectation that authority knew best and the working man knew his place that allowed Robens and the politicians to prevail and get away with their behaviours. The press did not campaign nor hold authority to account and the courts were not used to making and upholding appropriate remedial actions, as they often seem better able to do today. But it is the poor people of Aberfan I feel most for, many of whom lost everything and were so clearly failed before, during and after the tragedy, who nevertheless received no apology, much, if any, redress or indeed, any semblance of justice that we might reasonably expect today.